And in the evening, songs were sung in the tents and shelters, songs we shall never hear, for the real life of ancient times always escapes us. This corner of the ancient world had changed little with the coming of Christianity or with the coming of Theoderic and saw little reason to change. People took prosperity and social order for granted. The only cloud in this sunny scene was the king’s concern at reports that such a throng with goods and money might also attract marauders. He commanded the senator to whom the letter is addressed to convene the local landowners and farmers to ensure the security and tranquillity of the event. In this moment, they succeeded, and the Roman empire still lived.

Justinian`s world

The Empire That Couldn’t Help Itself (527 565)

Act two: In which, at a time of relative peace and prosperity, we meet a young, ambitious emperor who began life on the Balkan frontier, not far from modern Skopje in Macedonia, following a path to power paved by his enterprising uncle. When his uncle died, he took the throne and revealed ambitions for his capital and his empire on a scale that had not been seen since Constantine 200 years earlier. He won many battles and built many monuments—but that was not enough, for such zeal to preserve civilization can also prove unimaginably destructive.

Being Justinian

Justinian comes into history from out of shadows. We know how his uncle Justin came to Constantinople on foot to seek a military career and ended on the imperial throne. Justinian was the nephew who was the son Justin never had. Already in his thirties when we see him slipping into position next to his uncle’s new throne, he is a mystery to us until that time. At some point, he came down out of the Macedonian hinterlands to make his fortune, at some point he changed his name to emphasize his connection to the throne, and he acquired some of the skills of a prince. And he found himself a wife, Theodora mystical bulgaria tours.

Theodora haunts all the stories of Justinian, as virago, whore, mother superior, and great lady all at once. Hers is a character part, not a leading role, but she deserves an introduction separate from her husband. She was nothing by birth, in a world where birth was usually destiny. Her father kept bears in the circus at Constantinople, a world where shadows were dark enough to conceal a life of humiliation and sexual slavery for many a young woman.

A prudent telling of her story has her use proximity to power as opportunity, leading her into a series of liaisons with powerful men, one of whom turned into an emperor. But the stinging portrait of her in Procopius’s Anecdota (“Secret History”) goes far beyond the facts we can confirm otherwise to tell of her rise to power as a fallen woman, so to speak, ascending from common prostitute to pop celebrity to great courtesan to domineering empress. Her reportedly lurid sexual practices are so vividly reported in Procopius that Edward Gibbon congratulated himself on respecting his reader’s modesty by quoting them only in “the obscurity of a learned language”—the original Greek. The reader who wants to know the truth should read Procopius—did she really use geese to nibble the grains of wheat her handlers sprinkled over her nude body in her strip shows? Precisely what anatomical improbability did she imagine to expand her sexual pleasure? And there’s more. The effect of the public reputation of Theodora in Justinian’s lifetime and since is to give this humorless and indeed almost lifeless emperor a colorful and plausible counselor for his best and worst decisions. Her role is that of Nancy Reagan with a lurid past In governmental terms.

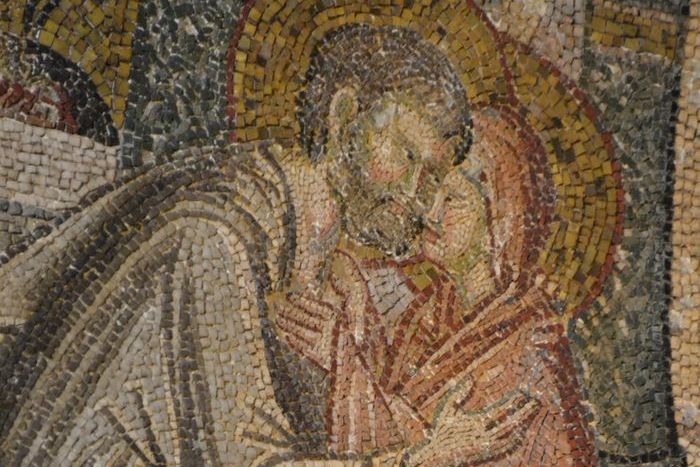

We know him best from one portrait, made when he was in his sixties and shimmering in colored mosaic stone on the walls of the church of San Vitale in Ravenna, a building he never saw in a city he never visited. Middle height, ordinary-looking, round-faced, brown-eyed—without the purple cloak and diadem, he could be like any other soldier turned courtier. He faces across the altar in San Vitale an equally famous portrait of Theodora. He has a bishop, clerics, and soldiers with him; she has attendants and great ladies, much more purple, and a cascade of jewels. Together they are bringing the bread and wine for the liturgy to unfold among the living on the altar below. The portraits capture them at a moment of high ceremonial drama, atypical in a way, but not so far from the truth—for the trappings and ceremony of empire meant that few people ever saw them except on display, self-consciously dramatic and seeking to make a great impression.