In governmental terms, a conservative observer would say that the provincial lines had been redrawn a bit, and new chief local rulers were in place in Africa, Spain, Italy-Provence, and northern Gaul. Since Diocletian around 300, the empire had been officiously divided into a series of larger and smaller units of organization, where the more than 100 provinces were aggregated into dioceses of a dozen or so provinces, and those in turn into four or more prefectures whose alignment would shift with political and military needs. The arrangement under the rulers of the late fifth century and the early sixth century looked more like a rearrangement than a revolution. More authority had devolved on leaders such as Theoderic and Clovis, but they in turn had recentralized at least some control from the multitude of smaller bureaucratic units of two centuries before. The chief variations from the imperial past were Italy’s power in southern Gaul and Rome’s abandonment of Britain.

In all respects, however, the provinces of the Roman empire from Gaul to Arabia, from Mauritania to Armenia, were in a better and more peaceful order than they had been for almost 100 years. What had changed was the scope, or scale, of Roman pretension and control. Theoderic, we have seen, praised the idea of empire but kept a firm grip on his own part of it. Had he been expressly offered an imperial crown by the soldiers, the senate, or Constantinople, he surely would have taken it, and he probably expected that either for himself or for his heirs.

In practical terms, if you sat in the palace in Constantinople in the fifth century, you had less western tax revenue at your disposal than before, but you also had less responsibility for defending wide swaths of territory that had long been a plague to maintain. Reasonable observers in Constantinople would probably have had interesting discussions and disagreements as to whether the trade-off was positive customized tour bulgaria.

It is true that something had been lost. The advantages of scale were real. The coherence of a culture and the freedom of movement and interaction of peoples were powerful by-products of the Roman Mediterranean hegemony. The world paid a real price for the violence that brought subjugation and discipline to peoples to secure that hegemony, but the victims of this imperialism had died 500 years ago and their suffering could reasonably if cold-bloodedly be written off against the benefits of empire. Whether the new world order of 526 could have, with different strategic choices, coalesced again into a more coherent Mediterranean community of nations is a question that cannot be answered.

MARKET DAY IN CALABRIA

Can we grasp a little of what life in the Italy Theoderic created was like away from cities and palaces? Here is a story from a letter that Cassiodorus wrote in the name of Theoderic’s grandson.

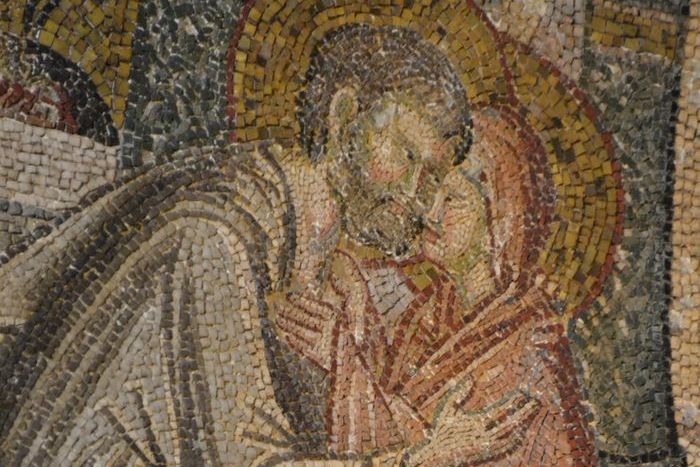

At a place called Consolinum, on the inland road from Naples south to Reggio di Calabria, the locals took over a spring that had been the site of an ancient religious festival—the Leucothea—to use as the site for a Christian baptistery.35 Or at least that was the official version of what happened. We cannot know for sure whether the residents set great store by such a transformation or whether they continued to think of and frequent the site much as their ancestors had done for centuries. But the natural springs on the site gave abundant pure water, fish boldly frolicking in them unaware that hungry fishermen would soon capture them. Leucothea, the white goddess and aunt of Dionysus, was a patron of initiations into religious cults long before anyone heard of Christianity.

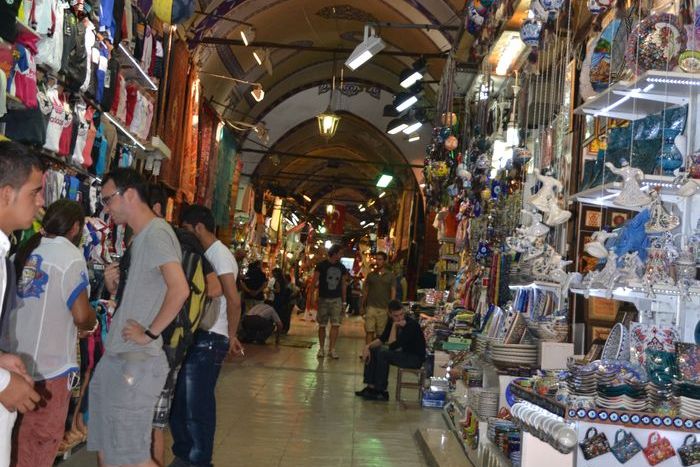

A market festival occurred there every year in mid-September for the feast of Cyprian, the martyred Christian bishop of Africa in the third century. This was the greatest market of the year, drawing merchants and buyers from Campania to Calabria and over to Apulia, virtually all of southern Italy. Some sellers erected stands and tents throughout the spreading meadows to display and protect their merchandise, while others cobbled together a temporary camp of shelters from tree branches to provide hospitality for all the visitors. It was a veritable city without buildings. Elegant clothes and handsome livestock, to say nothing of agricultural produce (it was harvest time, after all), were the great sellers, but the royal letter writer from whom we know of the event takes pains as well to describe and prettify something horrific: a brisk trade in children whose impoverished parents sold them into slavery. People could think it was better for children to be slaves in town than to live without food on their parents’ farms Skeptical historian Procopius of Constantinople.

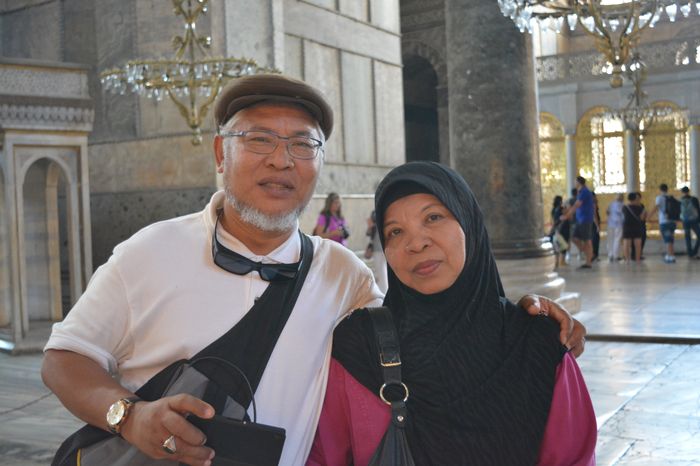

On the climactic night of the festival, we are told, when the priest or bishop began his prayers, the water in the baptismal spring sensed what was about to happen and rose exultantly to meet the prayers from above. A course of man-made steps led down into the spring, with the water regularly covering five of them, but the two higher steps remained dry, except when the prayers began and the water welled up spontaneously—miraculously—to facilitate the baptism.