This moralizing reading appears twenty years later, from the skeptical historian Procopius of Constantinople, and he burdens it with several overlays. It shows the Italian regime to disadvantage while preparing us for the claim that the barbarian regime was deteriorating and thus appropriately an object of military intervention from outside. The cartoonish barbarians who sent Athalaric to his grave with wine, women, and song are what one would expect in such a story, but these caricatures bear no resemblance to any Italian reality we know of. There were surely differences of opinion within the Italian court, and the young king could well have been a political football between factions, with his death an opportunity for blaming and posturing on all sides. The division is unlikely to have been between Roman and Goth; rather, it would have been between civilian and military, with the advocates of a strong defense seizing control of the young man’s future.

One short note: What should we think of Boethius? The fame of his popularized version of Plato in the Consolation in later centuries is real and his book stands on its merits. Its encouragement of quiet withdrawal from public life is in tune with a culture that would eschew ambition and wealth—at least in principle—but the message is at the very least controversial and worth controverting. Boethius’s actions and his career make sense in their place and time. If he grasped at the brass ring, missed, and then paid for his attempt with his life, he was no more and no less than a typical Roman aristocrat of any age and can scarcely be judged otherwise than as having misjudged his moment. Would Justinian have been happier to have Boethius in command in Italy than Theoderic’s heirs? Would Italy and later history have been spared some of Justinian’s mad restorationism ? The effort Boethius made, if it makes him out to be less an otherworldly philosopher than we have thought, might not have been so ill-advised as first appears coastal bulgaria holidays.

Theoderic`s death offers

Theoderic`s death offers an opportunity to take a deep breath and look around the Mediterranean at the state of the Roman empire in the year 526. This is arguably the last moment of genuinely ancient history when it makes sense to take collective stock like this, when the totality of what Rome created could still be thought of as one community.

The government that had begun doing business on seven hills in the Tiber valley in 753 BCE (the legendary date of Romulus’s founding of the city) or 509 BCE (the traditional date of the founding of the republic) was still fully alive and well and collecting taxes. It had moved its corporate headquarters to Constantinople almost exactly 200 years earlier, and flourished as a result. Two hundred years is a long time. At a distance of 1,500 years, many people, places, and events seem crowded close together by a foreshortening of the historical time line, but Constantine and his epochal changes (founding Constantinople, privileging Christianity) were as far in the past then as Napoleon and Thomas Jefferson are from us today.

This empire’s sway at the outermost boundaries of territory changed little in the eastern provinces. Though there had been military alarms and excursions in the Balkan provinces during the fifth century, at this moment the Danube frontier was no more and no less unsettled than at many other times since it had begun to be taken seriously as a boundary 500 years earlier. East of Constantinople, its boundaries with Persia were, if occasionally tested, mainly stable. South of Syria and around through Egypt and Cyrene, the long past of Roman dominion, which in turn continued Alexander’s heritage, now represented some 800 years of continual inclusion in the Mediterranean world Justinian`s world.

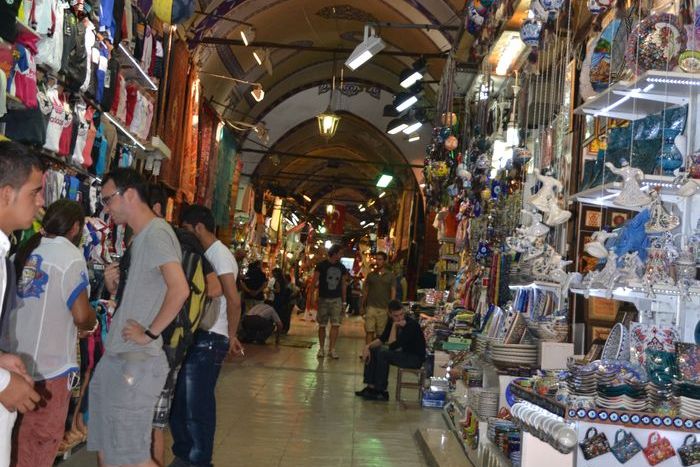

The world of people who spoke Latin had seen some changes, but those changes must not be overstated. The traditional cities dominated the traditional landscapes. The economic bases of these societies had not visibly changed—the same crops were being grown in the same places; the same markets were doing the same business. Cross-Mediterranean traffic from Carthage to Rome had fallen off—a fundamental fact of the age, but invisible to many. The Africans actually saw this as good news, for it meant that more wealth stayed home, untouched by taxation. Populations shrank and the world was not so prosperous as it once had been, but it was recognizably the same.